This year, I will write a shitty GUI for my Emacs clone

I’ve been hoping to write a GUI for my Emacs clone for a while now. And I’m putting together a list of Emacs’ display features to keep compatible with when designing the GUI. Unsurprisingly, this list just keeps growing, and, nah,

Waiting to feel ready to do the thing is not doing the thing. 1

So, I really need to start writing the shittiest Emacs GUI ever.

Of course, writing a blog post to announce “I will write a shitty GUI” is not doing the thing. But at least I get to partly explain “why Emacs redisplay is hard”, as is mentioned in a previous blog post.

1. How GNU Emacs renders¶

Since I do aim to be as compatible with GNU Emacs as possible, we will need to look into how Emacs does rendering, or, in other words, some of the largest C source files in Emacs:

emacs$ ls -Ssh src/*.c | head -n3

1.2M src/xdisp.c

956K src/xterm.c

532K src/sfnt.c

According to comments in these files, the 1.2 MB, 38k-line xdisp.c handles “display generation”, xterm.c provides “X window system support”, with “subroutines comprising the redisplay interface, setting up scroll bars and widgets, and handling input”, and sfnt.c is for TrueType format font support. So, indeed a huge part of Emacs’ C core goes to redisplay handling, and even trying to grasp a deeper understanding of it can take significant effort.

Fortunately, Emacs contributors have gifted us ample comments for us to gain a bird’s-eye view of Emacs’ rendering internals, like this architecure diagram:

+--------------+ redisplay +----------------+

| Lisp machine |---------------->| Redisplay code |<--+

+--------------+ (xdisp.c) +----------------+ |

^ | |

+----------------------------------+ |

Block input to prevent this when |

called asynchronously! |

|

note_mouse_highlight (asynchronous) |

|

X mouse events -----+

|

expose_frame (asynchronous) |

|

X expose events -----+

It looks quite simple, right?

1.1. Glyph matrix¶

Following the comments, we will then come across the central data structure in Emacs redisplay: glyph matrices, defined in dispextern.h. The authors have made it flexible enough to support three text rendering/layout scenarios: Emacs GUI windows, Emacs TUI frames, and Emacs buffer windows nested in TUI frames:

Each glyph matrix contains a bunch of glyph rows, whose contents are filled by display_line, which accepts a glyph iterator and repeatedly push the iterator forward, filling out glyph slot one by one.

It still sounds quite simple… until it doesn’t.

1.2. Bidirectional text display¶

It turns out that “pushing the glyph iterator forward” in display_line is just not as simple as it seems: not all texts are read from left to right, and the glyph iterator does not always move one character at a time. Here is an example:

(let ((ss '("star" "כוכב")))

(cons '("string" "0" "1" "2" "3")

(mapcar (lambda (s) `(,s . ,(mapcar #'string s))) ss)))

| string | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| star | s | t | a | r |

| כוכב | כ | ו | כ | ב |

Notice how "star" is rendered as s t a r (of course), but כוכב is rendered in a different order? The first Unicode character s[0] is כ, which is rendered at the rightmost column, while the second Unicode character s[1] (ו) is rendered as the third column counting from the left.

This is because the כוכב text is in Hebrew, which should be read from right to left. And when we mix English and Hebrew texts in the same line, any competent Unicode rendering engine will make sure that the Hebrew text is rendered from right to left. And that means, for right-to-left texts, our glyph iterator will need to jump until the end of that segment and iterate backwards.

I would describe this as a solved problem: Unicode has a well-defined algorithm for rendering bidirectional texts. However, Emacs’

bidi.cis around 120 kB, or around 4k lines, which still doesn’t include the code to pack and unpack a whole Unicode database. I guess that gives a good idea of how much work it might take to support bidirectional text in Emacs, if you don’t use an external library.

By the way, Emacs supports BIDI rendering even under terminal sessions, which I don’t think a lot of TUI programs are doing these days. That also makes me a bit ambivalent about discussions on some new, shiny TUI programs: many of them just don’t support BIDI rendering, and, depending on what they claim to do, that’s … quite telling.

1.3. Ligatures are a must¶

For some other languages, BIDI rendering is not enough. Their characters might “compose” into more complex glyphs, or, “ligatures”. For example, the following Arabic texts 2 must be rendered together as a single glyph to be readable for Arabic speakers:

Characters: “ड् ड ب س م”

Rendered: “ड्ड بسم”

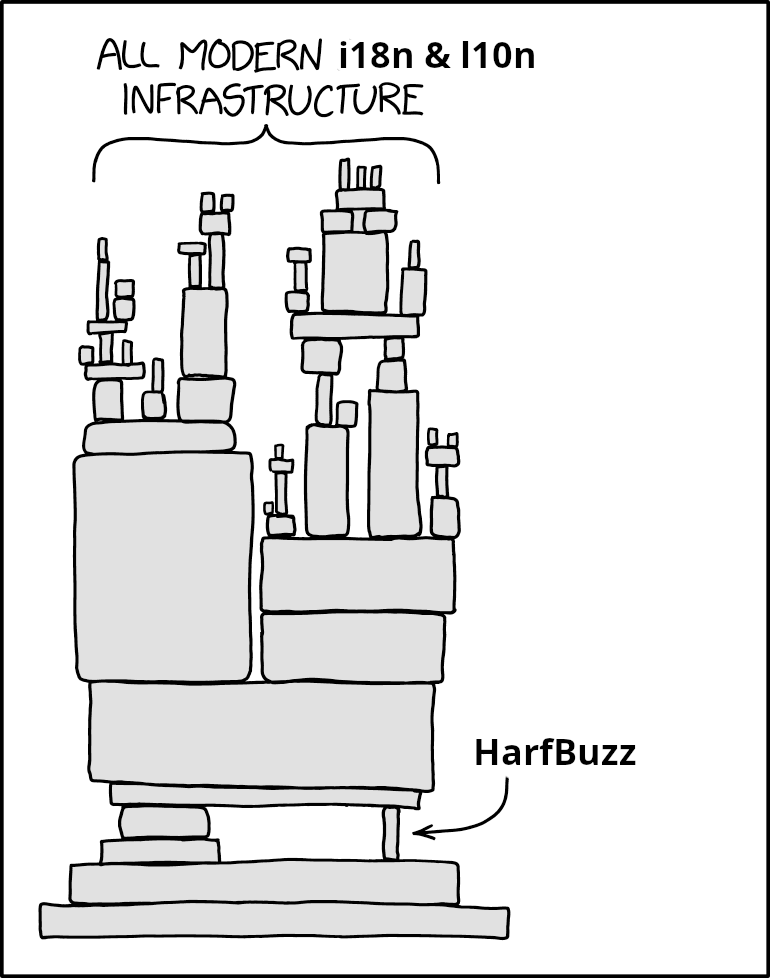

Supporting ligatures is not a simple matter. It has to know about the font(s) used, and thus needs to handle platform-specific font databases, support font fallback, etc., and have decent performance. The industry standard for this is the HarfBuzz library, and there is a reason that its home page references the xkcd “Dependency” meme:

Emacs also makes use of HarfBuzz, and does support ligatures. It’s only that, Emacs being Emacs, it allows you to customize the whole process, with Lisp code.

Taken from the famous Text Rendering Hates You post. If you haven’t read it, please please go and read it.

1.4. composition-function-table ¶

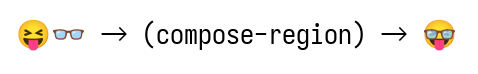

Emacs supports ligatures through its character compositions. When iterating through a glyph iterator, it calls composition_reseat_it to produce the corresponding composed glyphs (if any), and then walk the iterator into those glyphs. But, instead of directly delegating to HarfBuzz, Emacs checks composition-function-table first, where the user might put a regexp precondition and then any Lisp code to compose glyphs as they wish.

For some (or many?), this can be annoying since the default precondition regexps exclude most ligature combinations in programming fonts. For example,

- >will not compose into something like→even if you use a font like Fira Code. To support that, you will need to configure thecomposition-function-tablemanually, or use ligature.el.

1.5. Text properties¶

The above is only about text layout - what glyphs to use on screen, and where to place them. But, like any text rendering engine, of course Emacs allows you to style your text, with something called text properties. For example, by setting a proper face property for a text span, one can customize its font, size, colors, and text decorations. Also, there are some more self-explanatory properties, like invisible, line-height, line-prefix, or display-line-numbers-disable.

Basically, it’s just CSS for text, except that Emacs has made some parts of it … nearly Turing complete?

1.6. Lispy text properties¶

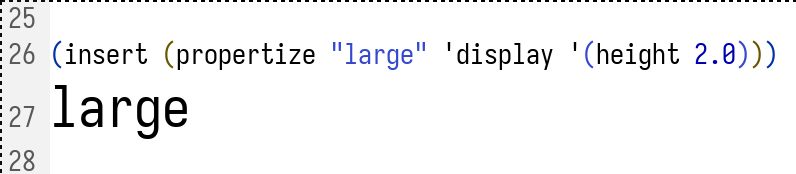

So, there is another text property called display, which can contain display properties. For example, with a string display property, the text span will be replaced by that string. For another, by setting a height display property, one can control the height of the texts:

And, by setting that height display property to a symbol…

… one can control the height of the texts dynamically, as the Emacs redisplay routine will now call the function pointed by that symbol for a height value.

1.7. Other features¶

-

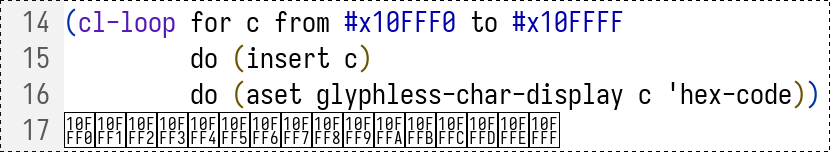

tab-width: Of course, you can control the tab width. - Character display control: Emacs lets you control how a character is displayed. This is orthogonal to text composition.

-

ctl-arrow: Non-nil means display control chars with uparrow ^, like^M. -

glyphless-char-display: For glyphless chars, one can display them by hex code, tofu boxes, etc.:

-

Display tables like

buffer-display-table: This allows you to override the display of characters in a buffer by replacing them with a string in the table.

Figure 5: One can even customize how new line characters look.

-

-

composition: Another special text property. One may use this to overlap glyphs together. This is purely visual and only works under GUI Emacs.

- Overlays: Lisp objects to “overlay” text properties on texts.

- Mode line: Emacs has a mode line for each buffer window, serving as a status bar. One may use an

:evalproperty to put custom content produced by arbitrary Lisp code into the mode line.

2. Why cloning Emacs redisplay behaviors is hard¶

I am quite sure that anyone reading this blog post can find some unexpected features of GNU Emacs’ redisplay. I’m not saying that those features are “problematic”, but during Emacs’ decades of evolution, people’s expectations certainly have changed.

It used to be fine to mix up computation and rendering when multi-threading wasn’t a thing; and now, everybody expects some concurrent rendering to make use of all those CPU cores. Terminals used to have quite limited support for characters, and display tables were helpful for converting undisplayable characters into something readable; but now, everything speaks Unicode, and display tables suddenly make little sense. Editors used to be all about texts; and now even terminals get to display images.

So, if you, people from modern times, are looking to copy Emacs’ redisplay behavior, things are going to be quite tricky. Concurrent display? What about those Turing complete text properties? They need to be run on the main thread. What about composition-function-table which also require running Lisp code?

It’s time to make some choices.

3. This year, I will …¶

First off, Juicemacs aims to be an exploratory Emacs clone. And for its GUI, I want to go to the extreme: it’s going to build on RPC/IPC protocols and push as much of the work to the client as possible. So, a shitty, minimally functional implementation will need:

3.1. Things I will not support¶

composition-function-table- New line character overrides through display tables or text properties

- Synchronous Lisp code execution from redisplay

3.2. Things that shitty GUI might support¶

- A buffer sync mechanism: texts, properties, and overlays.

- Proper display of propertized texts.

3.3. Things I do plan to support¶

- Sync mechanism for display tables and glyphless char display tables.

- Asynchronous Lisp code execution from redisplay (text properties & mode lines)

4. That’s it¶

Thanks for reading! If you have any feedback, any thoughts on a GUI design or some more unexpected Emacs features that I’ve overlooked, please let me know!

This blog post is also a submission to this month’s Emacs Carnival, theming “This year, I’ll …”. Check it out for more Emacsers’ Emacs plans!

Comments